John F. Kennedy

|

| Click Here to view the US Mint & Coin Acts 1782-1792 |

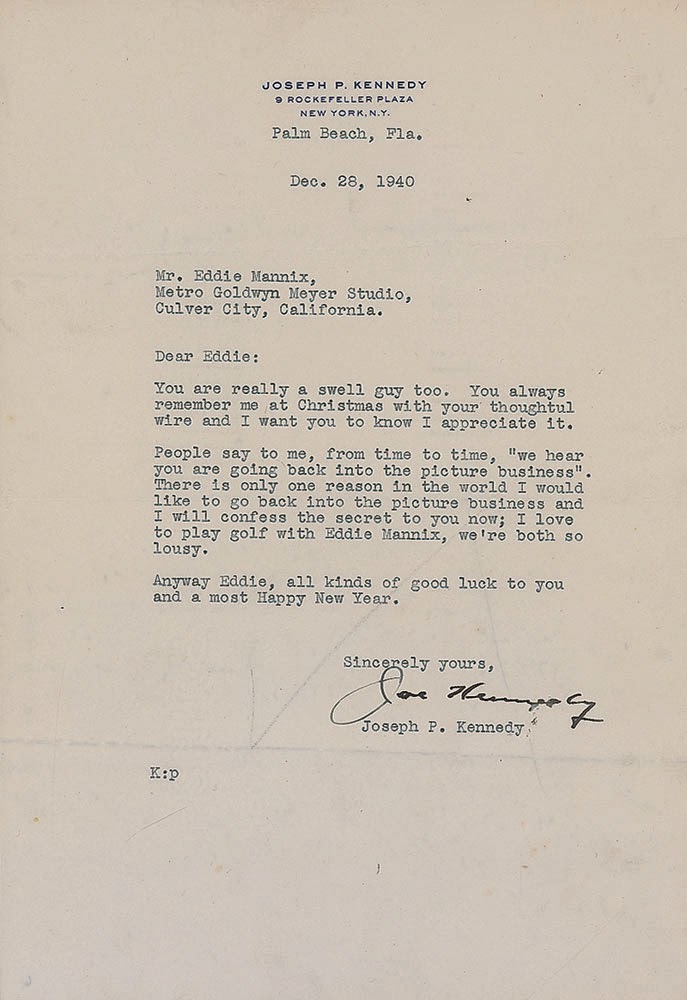

On October 7, 1914, Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald married Joseph Patrick "Joe" Kennedy Sr. after a seven-year courtship. Joseph was the elder son of Patrick Joseph "P. J." Kennedy, a political rival of Honey Fitz, Rose’s father. The couple first resided in Brookline, in the same home where their second child, John F. Kennedy, was born on May 29, 1917. This home is now preserved as the John Fitzgerald Kennedy National Historic Site.

|

| Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald Kennedy |

Kennedy had a happy childhood, though he often found himself overshadowed by his older brother, Joseph, who excelled in family competitions and academics. In contrast, young Kennedy struggled with frail health and recurring illnesses that frequently kept him out of school. Despite these challenges, he was a capable athlete. At age 13, Kennedy attended the private Canterbury School in New Milford, Connecticut, but illness forced him to leave. He later graduated from Choate Preparatory School in Wallingford, Connecticut, in 1935. That summer, he studied at the London School of Economics before enrolling at Princeton University. However, another bout of illness, jaundice, interrupted his studies, and he returned home during the Christmas break.

Kennedy resumed his education in the fall of 1936 at Harvard University, where he remained a laid-back student, focusing on swimming and, with his brother Joe, won the intercollegiate sailing championship. He made two additional trips to Europe in 1937 and 1939 while his father served as the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain. In 1940, Kennedy graduated cum laude from Harvard, and his undergraduate thesis, examining Britain's response to Germany's rearmament, was published as a book titled Why England Slept. After Harvard, he briefly attended Stanford University's Graduate School of Business in California.

On the night of August 2, 1943, Kennedy's PT Boat 109 was struck by a Japanese destroyer in the waters near New Georgia in the Solomon Islands. The collision threw Kennedy onto his back as the boat was split in half, killing two of the twelve crew members instantly. Kennedy quickly rallied the survivors, and they clung to the wreckage for hours, hoping for rescue. When rescue didn’t come, they swam three miles to a small island, with Kennedy towing an injured crew member, Pappy McNulty, by gripping the strap of his life jacket between his teeth. For four days, the men remained stranded on the island, while Kennedy swam daily along potential rescue routes used by American ships. Eventually, he encountered friendly natives on Cross Island, who delivered a message carved into a coconut shell to a U.S. infantry patrol. The crew was rescued, and Kennedy was awarded the Purple Heart and the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his heroism.

In a letter to Inga Arvad, a married woman he had met through his sister during the war, Kennedy reflected on the rescue:

"I received a letter today from the wife of my engineer, who was so badly burned that his face and hands and arms were just flesh, and he was that way for six days. He couldn't swim and I was able to help him, and his wife thanked me, and in her letter she said '...if he had died I don't think I would have wanted to go on living...' There are so many MacMahons that don't come through..."

The ordeal worsened Kennedy's back issues, and he contracted malaria, prompting his return to the U.S. for medical treatment. After undergoing back surgery, he was discharged in early 1945.

Initially, Kennedy's father, Joseph, had planned for his eldest son, Joseph Jr., to enter politics and eventually lead the family to the White House. However, Joseph Jr. was killed in action in 1944. Following a brief stint as a reporter for the Hearst International News Service, Kennedy decided to pursue politics himself. His opportunity came in 1946 when he announced his candidacy for the Democratic nomination for the House of Representatives in Massachusetts' 11th Congressional District. Running against nine other candidates, he won the primary with 42% of the vote. In November, he defeated his Republican opponent and became a congressman at age 29, winning reelection in 1948 and 1950. By 1952, Kennedy set his sights on the Senate, defeating Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. by more than 70,000 votes in a campaign that involved the entire Kennedy family.

On September 12, 1953, Kennedy married Jacqueline Lee Bouvier. The couple had three children: Caroline Bouvier (born in 1957), John Fitzgerald Jr. (1960–1999), and Patrick Bouvier, who tragically passed away less than 48 hours after his birth on August 7, 1963.

Kennedy’s back problems worsened, leading to spinal surgery. However, because he also suffered from Addison’s disease, the surgeries had to be performed in two stages—first in October 1954 and again in February 1955. During his lengthy recovery, Kennedy focused on writing Profiles in Courage, a book published in 1956 that won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 1957.

higher office. During the Democratic National Convention that year, he nearly secured the vice-presidential nomination alongside Adlai Stevenson, but lost on the third ballot to Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee. In 1958, Kennedy was re-elected to the Senate with the largest margin in Massachusetts’ history at the time. He gained national attention, speaking frequently across the country, and in January 1960, he formally announced his candidacy for president.

By the time of the Democratic National Convention, Kennedy had secured seven primary victories, dispelling doubts that a Roman Catholic could win in predominantly Protestant states. He won the party’s nomination, and the Kennedy/Lyndon B. Johnson ticket narrowly defeated the Republican candidates, Richard M. Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., in the November election by just 119,450 votes out of nearly 69 million cast.

John F. Kennedy as President-Elect, Criticizing Liberals

Autograph letter signed “Jack” to William S. White, journalist, biographer and friend of Lyndon Johnson. White had sent Kennedy some press clippings and Kennedy returned this note with his thanks. Dated December 1960, 2 pages on pale gray North Ocean Boulevard Palm Beach Florida letterhead, with accompanying envelope addressed, “Mr. William White.”

|

| President Dwight D. Eisenhower and President-Elect John F. Kennedy |

Transcript:SundayDear Bill:

They have forgotten that the root word is “liberalas” – or “free”. They have to themselves become imprisoned in the intense world of automatic responses.

All things look brighter here in the sun-

Jack

He appealed to foreign nations to join together to fight what he called the "common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself". He added: "All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin." In closing, he expanded on his desire for greater internationalism:

Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you.

|

| White House Photo: January 21, 1961, swearing-In Ceremony of President Kennedy's Cabinet |

Cabinet of President John

F. Kennedy (1961–1963)

|

||

Vice

President

|

Lyndon

B. Johnson (1961–1963)

|

|

Secretary

of State

|

Dean

Rusk (1961–1963)

|

|

Secretary

of the Treasury

|

C.

Douglas Dillon (1961–1963)

|

|

Secretary

of Defense

|

Robert

McNamara (1961–1963)

|

|

Attorney

General

|

Robert

F. Kennedy (1961–1963)

|

|

Postmaster

General

|

J.

Edward Day (1961–1963)

|

|

John

A. Gronouski (1963)

|

||

Secretary

of the Interior

|

Stewart

Udall (1961–1963)

|

|

Secretary

of Agriculture

|

Orville

Freeman (1961–1963)

|

|

Secretary

of Commerce

|

Luther

H. Hodges (1961–1963)

|

|

Secretary

of Labor

|

Arthur

Goldberg (1961–1962)

|

|

W.

Willard Wirtz (1962–1963)

|

||

Secretary

of Health, Education, and Welfare

|

Abraham

A. Ribicoff (1961–1962)

|

|

Anthony

J. Celebrezze (1962–1963)

|

||

|

October 10th, 1963, photograph of President John F. Kennedy Signing the Proclamation for the Interdiction of the Delivery of Offensive Weapons to Cuba |

The White House

January 20, 1961

To the Senate of the United States:

I nominate Dean Rusk, of New York, to be Secretary of State

I nominate Douglas Dillon, of New Jersey, to be Secretary of the Treasury.

I nominate Robert S. McNamara, of Michigan, to be Secretary of Defense.

I nominate Robert F. Kennedy, of Massachusettes, to be Attorney General.

I nominate J. Edward Day, of California, to be Postmaster General.

I nominate Stewart Lee Udall, of Arizona, to be Secretary of the Interior.

I nominate Orville L. Greeman, of Minnesota, to be Secretary of Argriculture.

I nominate Luther H. Hodges, of North Carolina, to be Secretary of Commerce.

I nominate Arthur J. Goldberg, of Illinois, to be Secretary of Labor.

I nominate Abraham Ribicoff, of Connecticut, to be Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare.

John F. Kennedy

In his commencement address at American University on June 10, 1963, Kennedy announced a new round of high-level arms negotiations with the Russians. He boldly called for an end to the Cold War. "If we cannot end our differences," he said, "at least we can help make the world a safe place for diversity." The Soviet government broadcast a translation of the entire speech, and allowed it to be reprinted in the controlled Soviet press.

In July 1963, Kennedy sent Averell Harriman to Moscow to negotiate a treaty with the Soviets. The introductory sessions included Khrushchev, who later delegated Soviet representation to Andrei Gromyko. It quickly became clear that a comprehensive test ban would not be implemented, due largely to the reluctance of the Soviets to allow inspections that would verify compliance. Ultimately, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union were the initial signatories to a limited treaty, which prohibited atomic testing on the ground, in the atmosphere, or underwater, but not underground; the U.S. Senate ratified this and Kennedy signed it into law in October 1963. France was quick to declare that it was free to continue developing and testing its nuclear defenses.

|

| John F. Kennedy signing the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty |

During the Eisenhower administration, as a follow-up to Project Mercury, the Apollo program was conceived and planned. Eisenhower'opposed a manned mission to the Moon and while his successor, John F. Kennedy, had an open mind despite his advisers maintaining that a Moon flight would be prohibitively expensive.Kennedy appointed Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had worked diligently in the US Senate to create NASA, chairman of the U.S. Space Council.

Kennedy, in his January 1961 State of the Union address, proposed Soviet and US cooperation in space but Premier Khrushchev declined holding Russian rocketry and space capabilities cards close to his vest. Three months later, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to fly in space demonstarting that in space technolgy, the US was fare behind the Soviet Union. Kennedy, eager for the U.S. effectively compete in the Space, surprised everyone announcing the goal of landing a man on the Moon in the speech to a Joint Session of Congress on May 25, 1961, stating:

"First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish." Full text Wikisource has information on "Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs"

This was followed with a speech at Rice University on September 12, 1962, in which he said:

"There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation many never come again. But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

It is for these reasons that I regard the decision last year to shift our efforts in space from low to high gear as among the most important decisions that will be made during my incumbency in the office of the Presidency."The following month in a cabinet meeting with NASA administrator James E. Webb Johnson assured the President that lessons learned from the costly space program would have important scientific value. The projected $40 billion cost of the Apollo program, Johnson also maintained, was not just an expenditure just to enhance US international prestige but would be of great military value.

Despite Johnson wanting to keep the program in house, Kennedy was still interested in a joint venture Apollo program with the Soviet Union. NASA reports:

On September 18th, 1963, the President met briefly with NASA Chief James Webb. Kennedy told him that he was thinking of pursuing the topic of cooperation with the Soviets as part of a broader effort to bring the two countries closer together. He asked Webb, "Are you sufficiently in control to prevent my being undercut in NASA if I do that?" As Webb remembered that meeting, "So in a sense he didn't ask me if he should do it; he told me he thought he should do it and wanted to do it. . . ." What he sought from Webb was the assurance that there would be no further unsolicited comments from within the space agency. Webb told the President that he could keep things under control.

Late on the following day, Bundy called Webb to tell him that the President had decided to include a statement about space cooperation with the Soviets in his U.N. address. Bundy informed Webb that Kennedy wanted "to be sure that you know about it." The new paragraph, drafted by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., another Kennedy aide, had not been included in the earlier drafts of the speech circulated at NASA.65 Upon receiving the President's message, Webb immediately telephoned directions to the various NASA centers "to make no comment of any kind or description on this matter."

The President's proposal for a joint expedition to the moon was intended to be a step toward improved Soviet-American relations. The impact of the speech was quite the reverse. Moscow and the Soviet press virtually ignored the U.N. address. Officially, the Soviet government did not comment. In the U.S., the public remarks either strongly supported the idea of a joint flight or equally forcefully opposed it.On July 20, 1969, almost six years after Kennedy's death, Apollo 11 landed the first manned spacecraft on the Moon without any help from the Soviet Union.

|

| John F. Kennedy with Caroline Kennedy Halloween in the Oval Office |

Tensions eased somewhat with the Soviets with the 1963 nuclear test ban treaty, although the “space race” continued. Kennedy was a strong supporter of the arts, while being mindful of the disadvantaged. He and his wife attempted to make the White House the cultural center of the nation. He was an avid reader and was particularly interested in what the press had to say about his administration. He founded the Peace Corps and proposed wide-ranging civil rights legislation, but never lived to see its enactment.

|

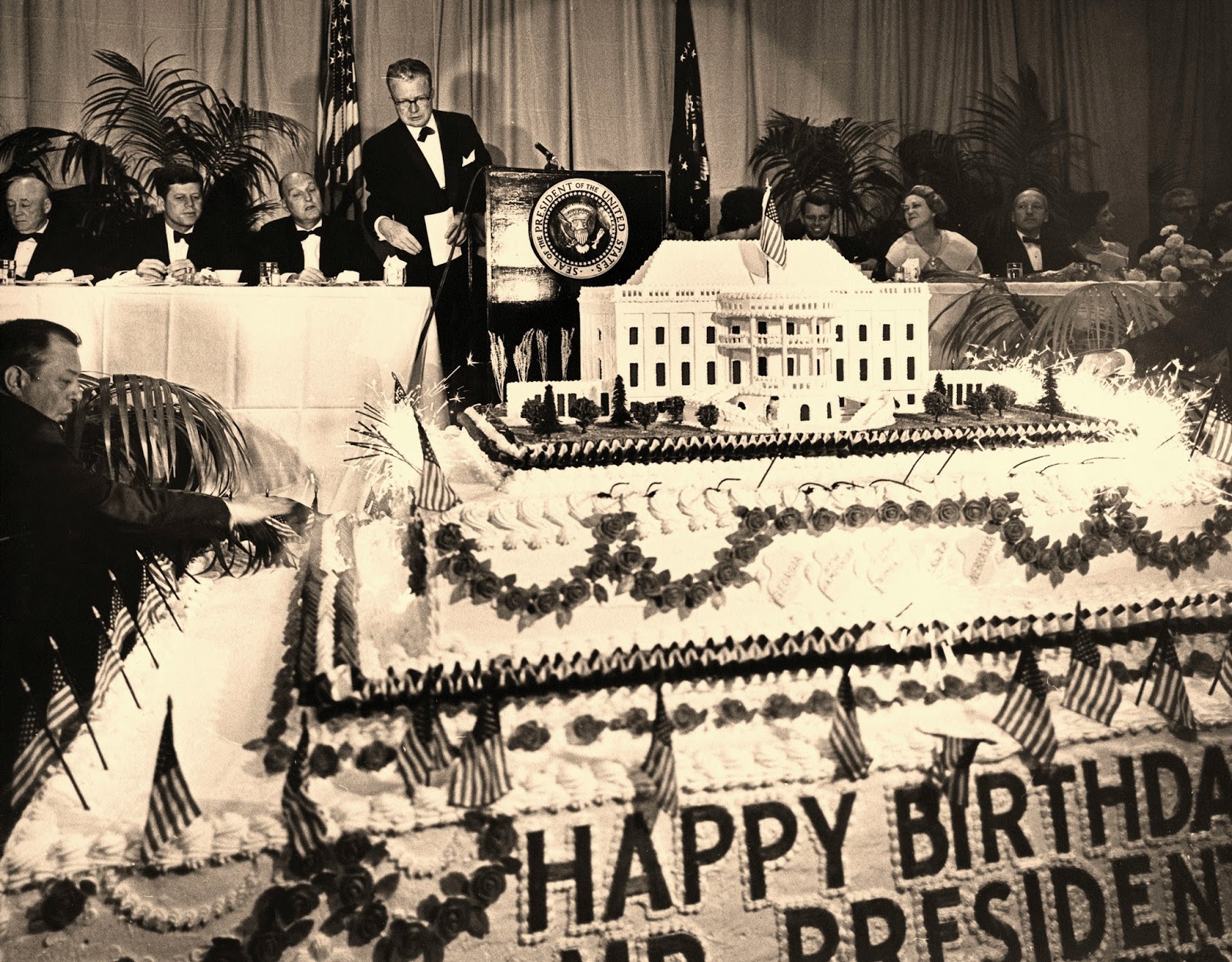

December 6th, 1962, Kennedy Foundation Awards Banquet. Mrs. Joseph P. Kennedy (Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy) and President Kennedy at the Statler Hilton Hotel, Washington, D.C |

In the spring of 1963, the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and Martin Luther King, Jr., launched a civil rights mass protest in Birmingham, Alabama, which King called the most segregated city in America. Initially, the demonstrations had little impact. Then, on Good Friday, King was arrested and spent a week behind bars. While in was jail eight clergyman wrote him a letter criticizing his work as unwise and wrong. Dr. King responded to the clergymen in an open letter, written on April 16, 1963. This "Letter From A Birmingham Jail" is now one of the most celebrated documents in United States history. The letter not only defends the strategy of nonviolent resistance to racism, but also argues that people have a moral responsibility to break unjust laws, where he wrote one of his most famous meditations on racial injustice and civil disobedience, "Letter from Birmingham Jail."

Meanwhile, James Bevel, one of King's young lieutenants, summoned black youths to march in the streets at the beginning of May. The Birmingham City Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor used police dogs and high-pressure fire hoses to put down the demonstrations. Nearly a thousand young people were arrested. The violence was broadcast on television to the nation and the world and the "Letter from Birmingham Jail." received national media attention. Invoking federal authority, President Kennedy sent several thousand troops to an Alabama air base, and his administration responded by speeding up the drafting of a comprehensive civil rights bill.

More than 200,000 Americans of all races celebrated the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation by joining the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Key civil rights figures led the march, including A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Bayard Rustin, and Whitney Young. But the most memorable moment came when Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

In the fall, the comprehensive civil rights bill cleared several hurdles in Congress and won the endorsement of House and Senate Republican leaders. It was not passed, however, before the November 22, 1963 assassination of President Kennedy. The Civil Rights Act was left in the hands of the new President, Lyndon B. Johnson.

President Johnson's 20 years of experience as a Texas Congressman and a US Senator enabled him to capitalize on his connections with his fellow southern white congressional leaders. This legislative expertise, coupled with nearly 90% Republican Congressional support and the outpouring of public emotion, enabled Johnson to coral a super majority of US Senators to break the Democratic Party's filibuster against the Civil Rights Act.

The provisions of the Civil Rights Act passed on July 2nd, 1964, included:

- protecting African Americans against discrimination in voter qualification tests;

- outlawing discrimination in hotels, motels, restaurants, theaters, and all other public accommodations engaged in interstate commerce;

- authorizing the U.S. Attorney General's Office to file legal suits to enforce desegregation in public schools;

- authorizing the withdrawal of federal funds from programs practicing discrimination;

- outlawing discrimination in employment in any business exceeding 25 people and creating an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to review complaints.

Assassination:

On November 22, 1963, while on his way to make a luncheon speech in Dallas, Texas, Kennedy and his wife sat in an open convertible waving to the crowds who had gathered to greet him. Suddenly, as the motorcade approached an underpass, an assassin fired several shots, striking the President in the neck and head.

|

John F. Kennedy Funeral Protocol Instructions, ten pages Courtesy of The U.S. Presidency & Political Hospitality

|

|

John F. Kennedy Funeral Motorcade Instructions, six pages Courtesy of The U.S. Presidency & Political Hospitality

|

Continental Congress of the United Colonies Presidents

September 5, 1774

|

October 22, 1774

| |

October 22, 1774

|

October 26, 1774

| |

May 20, 1775

|

May 24, 1775

| |

May 25, 1775

|

July 1, 1776

|

Continental Congress of the United States Presidents

July 2, 1776 to February 28, 1781

July 2, 1776

|

October 29, 1777

| |

November 1, 1777

|

December 9, 1778

| |

December 10, 1778

|

September 28, 1779

| |

September 29, 1779

|

February 28, 1781

|

March 1, 1781 to March 3, 1789

March 1, 1781

|

July 6, 1781

| |

July 10, 1781

|

Declined Office

| |

July 10, 1781

|

November 4, 1781

| |

November 5, 1781

|

November 3, 1782

| |

November 4, 1782

|

November 2, 1783

| |

November 3, 1783

|

June 3, 1784

| |

November 30, 1784

|

November 22, 1785

| |

November 23, 1785

|

June 5, 1786

| |

June 6, 1786

|

February 1, 1787

| |

February 2, 1787

|

January 21, 1788

| |

January 22, 1788

|

January 21, 1789

|

(1789-1797)

|

(1933-1945)

| |

(1865-1869)

| ||

(1797-1801)

|

(1945-1953)

| |

(1869-1877)

| ||

(1801-1809)

|

(1953-1961)

| |

(1877-1881)

| ||

(1809-1817)

|

(1961-1963)

| |

(1881 - 1881)

| ||

(1817-1825)

|

(1963-1969)

| |

(1881-1885)

| ||

(1825-1829)

|

(1969-1974)

| |

(1885-1889)

| ||

(1829-1837)

|

(1973-1974)

| |

(1889-1893)

| ||

(1837-1841)

|

(1977-1981)

| |

(1893-1897)

| ||

(1841-1841)

|

(1981-1989)

| |

(1897-1901)

| ||

(1841-1845)

|

(1989-1993)

| |

(1901-1909)

| ||

(1845-1849)

|

(1993-2001)

| |

(1909-1913)

| ||

(1849-1850)

|

(2001-2009)

| |

(1913-1921)

| ||

(1850-1853)

|

(2009-2017)

| |

(1921-1923)

| ||

(1853-1857)

|

(20017-Present)

| |

(1923-1929)

|

*Confederate States of America

| |

(1857-1861)

| ||

(1929-1933)

| ||

(1861-1865)

|

United Colonies Continental Congress

|

President

|

18th Century Term

|

Age

|

Elizabeth "Betty" Harrison Randolph (1745-1783)

|

09/05/74 – 10/22/74

|

29

| |

Mary Williams Middleton (1741- 1761) Deceased

|

Henry Middleton

|

10/22–26/74

|

n/a

|

Elizabeth "Betty" Harrison Randolph (1745–1783)

|

05/20/ 75 - 05/24/75

|

30

| |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

05/25/75 – 07/01/76

|

28

| |

United States Continental Congress

|

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

07/02/76 – 10/29/77

|

29

| |

Eleanor Ball Laurens (1731- 1770) Deceased

|

Henry Laurens

|

11/01/77 – 12/09/78

|

n/a

|

Sarah Livingston Jay (1756-1802)

|

12/ 10/78 – 09/28/78

|

21

| |

Martha Huntington (1738/39–1794)

|

09/29/79 – 02/28/81

|

41

| |

United States in Congress Assembled

|

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

Martha Huntington (1738/39–1794)

|

03/01/81 – 07/06/81

|

42

| |

Sarah Armitage McKean (1756-1820)

|

07/10/81 – 11/04/81

|

25

| |

Jane Contee Hanson (1726-1812)

|

11/05/81 - 11/03/82

|

55

| |

Hannah Stockton Boudinot (1736-1808)

|

11/03/82 - 11/02/83

|

46

| |

Sarah Morris Mifflin (1747-1790)

|

11/03/83 - 11/02/84

|

36

| |

Anne Gaskins Pinkard Lee (1738-1796)

|

11/20/84 - 11/19/85

|

46

| |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

11/23/85 – 06/06/86

|

38

| |

Rebecca Call Gorham (1744-1812)

|

06/06/86 - 02/01/87

|

42

| |

Phoebe Bayard St. Clair (1743-1818)

|

02/02/87 - 01/21/88

|

43

| |

Christina Stuart Griffin (1751-1807)

|

01/22/88 - 01/29/89

|

36

|

Constitution of 1787

First Ladies |

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797

|

57

| ||

March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1801

|

52

| ||

Martha Wayles Jefferson Deceased

|

September 6, 1782 (Aged 33)

|

n/a

| |

March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817

|

40

| ||

March 4, 1817 – March 4, 1825

|

48

| ||

March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1829

|

50

| ||

December 22, 1828 (aged 61)

|

n/a

| ||

February 5, 1819 (aged 35)

|

n/a

| ||

March 4, 1841 – April 4, 1841

|

65

| ||

April 4, 1841 – September 10, 1842

|

50

| ||

June 26, 1844 – March 4, 1845

|

23

| ||

March 4, 1845 – March 4, 1849

|

41

| ||

March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850

|

60

| ||

July 9, 1850 – March 4, 1853

|

52

| ||

March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1857

|

46

| ||

n/a

|

n/a

| ||

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865

|

42

| ||

February 22, 1862 – May 10, 1865

| |||

April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869

|

54

| ||

March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877

|

43

| ||

March 4, 1877 – March 4, 1881

|

45

| ||

March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881

|

48

| ||

January 12, 1880 (Aged 43)

|

n/a

| ||

June 2, 1886 – March 4, 1889

|

21

| ||

March 4, 1889 – October 25, 1892

|

56

| ||

June 2, 1886 – March 4, 1889

|

28

| ||

March 4, 1897 – September 14, 1901

|

49

| ||

September 14, 1901 – March 4, 1909

|

40

| ||

March 4, 1909 – March 4, 1913

|

47

| ||

March 4, 1913 – August 6, 1914

|

52

| ||

December 18, 1915 – March 4, 1921

|

43

| ||

March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923

|

60

| ||

August 2, 1923 – March 4, 1929

|

44

| ||

March 4, 1929 – March 4, 1933

|

54

| ||

March 4, 1933 – April 12, 1945

|

48

| ||

April 12, 1945 – January 20, 1953

|

60

| ||

January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961

|

56

| ||

January 20, 1961 – November 22, 1963

|

31

| ||

November 22, 1963 – January 20, 1969

|

50

| ||

January 20, 1969 – August 9, 1974

|

56

| ||

August 9, 1974 – January 20, 1977

|

56

| ||

January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981

|

49

| ||

January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989

|

59

| ||

January 20, 1989 – January 20, 1993

|

63

| ||

January 20, 1993 – January 20, 2001

|

45

| ||

January 20, 2001 – January 20, 2009

|

54

| ||

January 20, 2009 to date

|

45

|

Philadelphia

|

Sept. 5, 1774 to Oct. 24, 1774

| |

Philadelphia

|

May 10, 1775 to Dec. 12, 1776

| |

Baltimore

|

Dec. 20, 1776 to Feb. 27, 1777

| |

Philadelphia

|

March 4, 1777 to Sept. 18, 1777

| |

Lancaster

|

September 27, 1777

| |

York

|

Sept. 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778

| |

Philadelphia

|

July 2, 1778 to June 21, 1783

| |

Princeton

|

June 30, 1783 to Nov. 4, 1783

| |

Annapolis

|

Nov. 26, 1783 to Aug. 19, 1784

| |

Trenton

|

Nov. 1, 1784 to Dec. 24, 1784

| |

New York City

|

Jan. 11, 1785 to Nov. 13, 1788

| |

New York City

|

October 6, 1788 to March 3,1789

| |

New York City

|

March 3,1789 to August 12, 1790

| |

Philadelphia

|

Dec. 6,1790 to May 14, 1800

| |

Washington DC

|

November 17,1800 to Present

|

Hosted by The New Orleans Jazz Museum and The Louisiana Historical Center

A Non-profit Corporation

202-239-1774 | Office

202-239-0037 | FAX

Dr. Naomi and Stanley Yavneh Klos, Principals

|

| U.S. Dollar Presidential Coin Mr. Klos vs Secretary Paulson - Click Here |

The United States of America Continental Congress Presidents (1776-1781)

The United States of America in Congress Assembled Presidents (1781-1789)

The United States of America Presidents and Commanders-in-Chiefs (1789-Present)